Throughout the course of their lives, people form romantic relationships, which may involve dating, cohabiting, or marrying. Recognizing the centrality of these relationships to people’s lives—and the benefits of healthy relationships to individual, couple, and child well-being—some social service agencies have invested in programs designed to support healthy relationships and marriage. 1 Research shows that the formation and stability of romantic relationships have changed considerably over time. The purpose of this brief is to provide an update on these topics for the research community, as well as a concise review for practitioners.

This brief is the first in a series examining the state of the field of research on romantic relationships. In this series, we review what existing research tells us about the types of romantic relationships that people form, the stability of these relationships over time, and how these patterns vary by important sociodemographic characteristics, such as socioeconomic status or race/ethnicity. This first brief details recent demographic trends in dating, cohabitation, and marriage for the population as a whole in the United States. We present common definitions of these relationship types, provide an overview of how researchers measure them, and review published estimates and trends across various dimensions of these unions (e.g., age at first marriage, prevalence of marriage, and rate of marriage among unmarried individuals). We additionally review existing research on patterns of union dissolution over time.

The research reviewed for this brief allows us to detail trends over 25 years or more, generally up through the 2010s. However, the time periods examined may not be consistent across all measures since estimates are limited to the available research data. Additionally, discussions of romantic relationships in this brief are limited to different-gender relationships due to a paucity of published research on trends in relationship formation and dissolution among same-gender relationships.

Over the past several decades, patterns of union formation and dissolution in the United States have

changed in notable ways.

As these key findings indicate, patterns of dating, cohabitation, marriage, and divorce continue to change and evolve, presenting new challenges and opportunities for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners alike.

Dating represents an important stage in the lives of adolescents and young adults. Specifically, dating experiences have been linked to a range of outcomes, including the development of romantic identities, the state of adolescents’ mental well-being, and their relationship quality later in life. 2 In this section, we present research on the shares of adolescents and young adults who have been or are currently dating, and summarize new research on the use of the internet to meet new partners. Much of the information comes from a few key data sources, including the Monitoring the Future survey, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), and the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study.

Examining trends in dating can be challenging because the meaning of dating has changed over time and because different surveys do not measure dating relationships in the same way. 3 Some surveys, for example, ask about being “involved in a romantic or sexual relationship” (Add Health), while others ask about “how often [respondents] go out with a date” (Monitoring the Future). Survey questions that define dating broadly, such as “when you like a guy [girl] and he [she] likes you back” (Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study), 4 capture both casual and serious romantic relationships. However, narrower definitions, such as “romantic or sexual relationships” (Add Health), may only capture more serious or formal dating relationships.

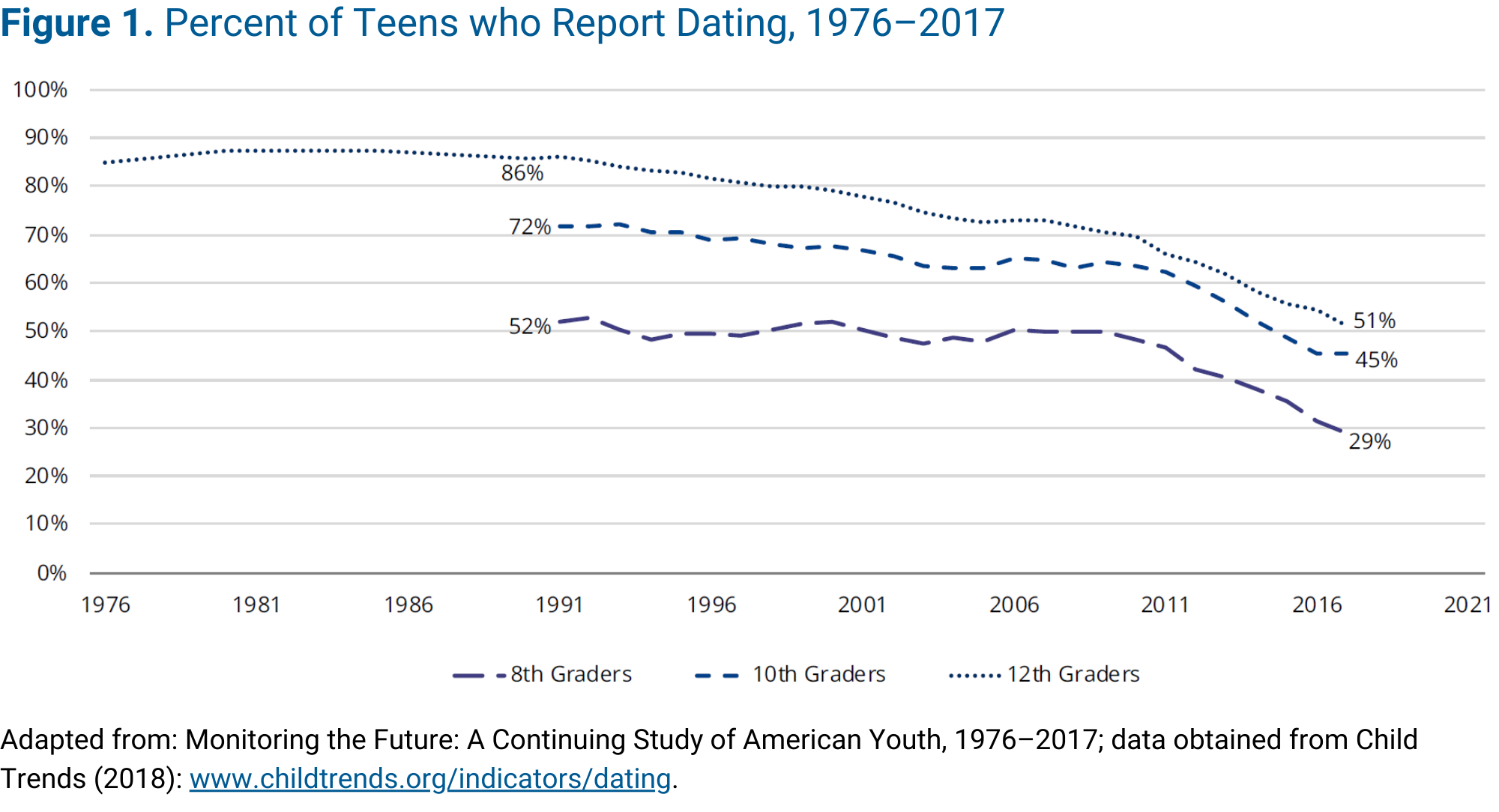

Most adolescents today will experience some sort of dating relationship by the time they reach early adulthood. 5 Figure 1 presents the share of adolescents who reported dating from 1976 to 2017. About 51 percent of high school seniors reported dating in 2017, which represents a decline from 2001 when about 78 percent of high school seniors dated. 6 Some of the reduction in the share of teens who date may reflect changing terminology used to describe dating relationships. As more recent cohorts develop new terms to describe these relationships, the terminology used by prior generations may not reflect how current teens characterize their experiences. As a result, the apparent decline in the share who report dating may, to some extent, overstate the actual change due to shifting vernacular. 7

Differences in dating by age are not always straightforward to interpret. For instance, compared to teens and those in their early twenties, dating is less common among young adults ages 24 to 32, at about 23 percent in 2007–2008, but this difference is largely due to the fact that men and women in this age range more often live with a romantic partner or are married (discussed below). Among those who are dating, however, both teens and young adults (ages 24 to 32) characterize their relationships as serious, though perhaps in different ways. 8 In 2014–2015, nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of adolescents who were currently dating described their relationship as serious. 9 Similarly, a large majority of young adults’ dating relationships are serious: In 2007–2008, of young adults ages 24 to 32 in dating relationships, 70 percent reported dating exclusively or being engaged. 8

Research shows that the internet has become an important factor in relationship formation. During the 1990s, very few adult couples met online, but by 2009 about 20 percent of different-gender couples did so. 10 As the internet became a more common way for couples to meet, other pathways to dating relationships—such as meeting through friends, family, and school—became less salient; by 2013, meeting online was the most common way for different-gender couples to meet, with more than a quarter of couples meeting through the internet. 11 Meeting online became increasingly common, with 39 percent of adult couples meeting online in 2017. 11 Among adolescents, meeting a romantic partner online was slightly less common, with about 23 percent of teens (ages 13 to 17) who ever dated by 2014–2015 having met a romantic partner online. 9

The rise in cohabitation has been an important part of the change in family formation patterns in recent decades. Cohabitation is defined as a romantic union between two unmarried partners living together in the same household. 12 Cohabiting partners have fewer legal rights and responsibilities compared with married couples; for example, unlike married spouses, cohabiting partners have little right to property or economic resources in the event of a separation. 13 At the same time, social support for cohabitation is strong, with the majority of adults believing it is acceptable for unmarried couples to live together. 14 Further, many young people believe that it is a good idea for a couple to live together before marrying in order to test the compatibility of the relationship, and 74 percent of women agree that it is acceptable to have and raise children in cohabiting unions. 15, 16 However, compared to marriages, cohabiting unions are less stable, and children born to cohabiting parents experience three times as many family transitions (i.e., change in parent’s union status) than children born to married parents. 17 As with marriage, couples primarily enter into cohabitation for love and companionship, but a substantial minority of couples also report cohabiting for financial and convenience reasons; this suggests that cohabitation may serve a unique purpose for some men and women. 14

Below we review recent estimates and trends in cohabitation in the United States. Relying on existing published research, we review 1) the prevalence of cohabitation, 2) the average age at first cohabitation, 3) when and how cohabiting relationships end (i.e., whether they transition to marriage or they dissolve), and 4) the prevalence of serial cohabitation (i.e., the proportion of people who cohabit more than once). While we reviewed results of several surveys, the literature cited primarily relies on data from two nationally representative family surveys: the National Survey of Family Growth and the National Survey of Families and Households.

As with dating, there can be some variation in how cohabitation is measured across surveys. Questions used by recent surveys to assess cohabitation status at the time of the interview as well as prior cohabitation experiences include (but are not limited to):

Some surveys (such as the Survey of Income and Program Participation) also use lists of household members (i.e., household rosters), and their relationships to one another (“unmarried partner”), to establish cohabitation status. 18

These differences in the various questions and methods used to study cohabitation have resulted in some inconsistencies in estimates of cohabitation experiences within the literature. 18–20 Furthermore, prior to 2002, one of the primary data sources of cohabitation (and marriage) trends, the National Survey of Family and Growth, interviewed only women. As a result, many of the trends described in this brief—and in the larger literature—focus on women’s union status and experiences.

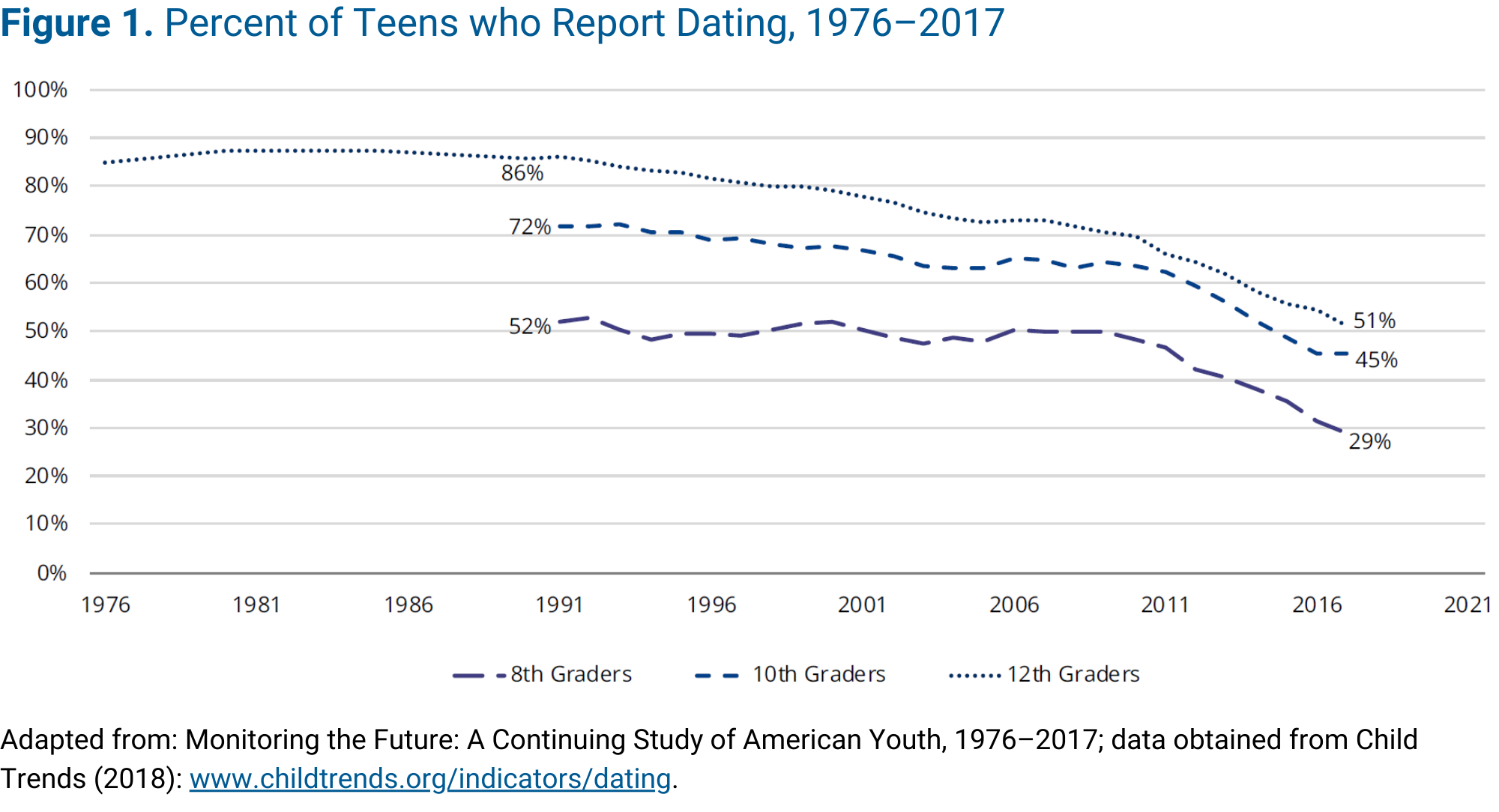

The percentage of adults who have ever cohabited has nearly doubled in recent decades. As shown in Figure 2, in 1987 about one-third of women ages 19 to 44 had ever cohabited, whereas nearly two-thirds of women had done so in 2013. 21

As cohabitation has become more common, the share of marriages preceded by cohabitation between future spouses has increased. Seventy percent of women who first married in 2010 to 2014, for example, lived with their husband prior to marriage, whereas just 40 percent of those who married in 1980 to 1984 had done so. 22

While the prevalence of cohabitation has increased, the median age at which men and women first form a coresidential union—either marriage or cohabitation—has not changed much over time. Additionally, the age at first cohabitation has remained relatively stable in recent decades: From 1983–1988 to 2006–2010, the median age of entry into cohabitation declined only slightly, from age 22.8 to 21.8 among women and from age 23.9 to 23.5 among men. 23

Cohabiting unions can end in one of two ways: Partners can either break up or transition into marriage. The share of cohabitations that transition to marriage has declined over the past 30 years. Research shows that two-fifths (42 percent) of women who were cohabiting in the mid- to late-1980s married their first cohabiting partner within five years of moving in together, compared to only about one-fifth (22 percent) of women who cohabited at some point from 2006 to 2013. 24 Most cohabiting couples who marry will do so within three years of the start of the cohabitation. 24

At the same time, the share of cohabitations ending in dissolution has remained essentially unchanged. Research finds that 35 percent of cohabitations formed during 1983–1988 and 36 percent of those formed in 2006–2013 ended in separation within five years. 24

These simultaneous trends reflect the fact that couples are maintaining cohabiting unions longer. The overall duration of cohabiting unions has been steadily rising. 24, 25 In the mid-1980s, for example, first cohabitations lasted an average of 12 months, and this rose to about 18 months for cohabitations formed between 2006 and 2013. 24

Many people who cohabit and then break up go on to form another cohabiting union with a new partner. Forming these second, third, and higher cohabiting unions with different partners is termed serial cohabitation.

Serial cohabitation has become more common over time. Among women born from 1960 to 1964 who first cohabited during young adulthood, about 60 percent entered a second cohabiting union within 12 years of the end of their first cohabitation. For women born 20 years later (1980–1984), 73 percent had entered a new cohabiting union within 12 years of their first cohabitation dissolution. 26 Furthermore, the time elapsed between the end of one cohabitation and the start of another has decreased for more recent cohorts. Among women who had two or more cohabitations, those born from 1980 to 1984 entered into a second cohabiting union just 26 months, on average, after the end of their first cohabitation, whereas women born in 1960 to 1964 took an average of 47 months to enter such a union. 26

Despite changes in the prevalence and timing of marriage in recent decades (detailed below), marriage remains a central and symbolically significant experience in many Americans’ lives. Young adults, for example, prioritize being married slightly more than other future roles, such as being a parent or having a career, and 75 percent of graduating high school seniors expect to marry. 27, 28

In this section, we draw from published research to summarize estimates and trends in 1) the share of individuals currently married and ever married, 2) individuals’ age at first marriage, 3) marriage rates, and 4) remarriage rates. Marital dissolution—divorce—is discussed in a separate section. These estimates primarily rely on data from the American Community Survey, the Current Population Survey, and the National Survey of Family Growth.

Marriage refers to a legally recognized partnership between two individuals, often involving a public expression of commitment. Since marriage is a legal status, the measurement of marriage is less complex than the measurement of dating or cohabitation. However, as with cohabitation, much of the research on marriage trends relies on women’s reports due to data limitations. 29 Here, we summarize available research on marriage trends, incorporating data on men whenever possible.

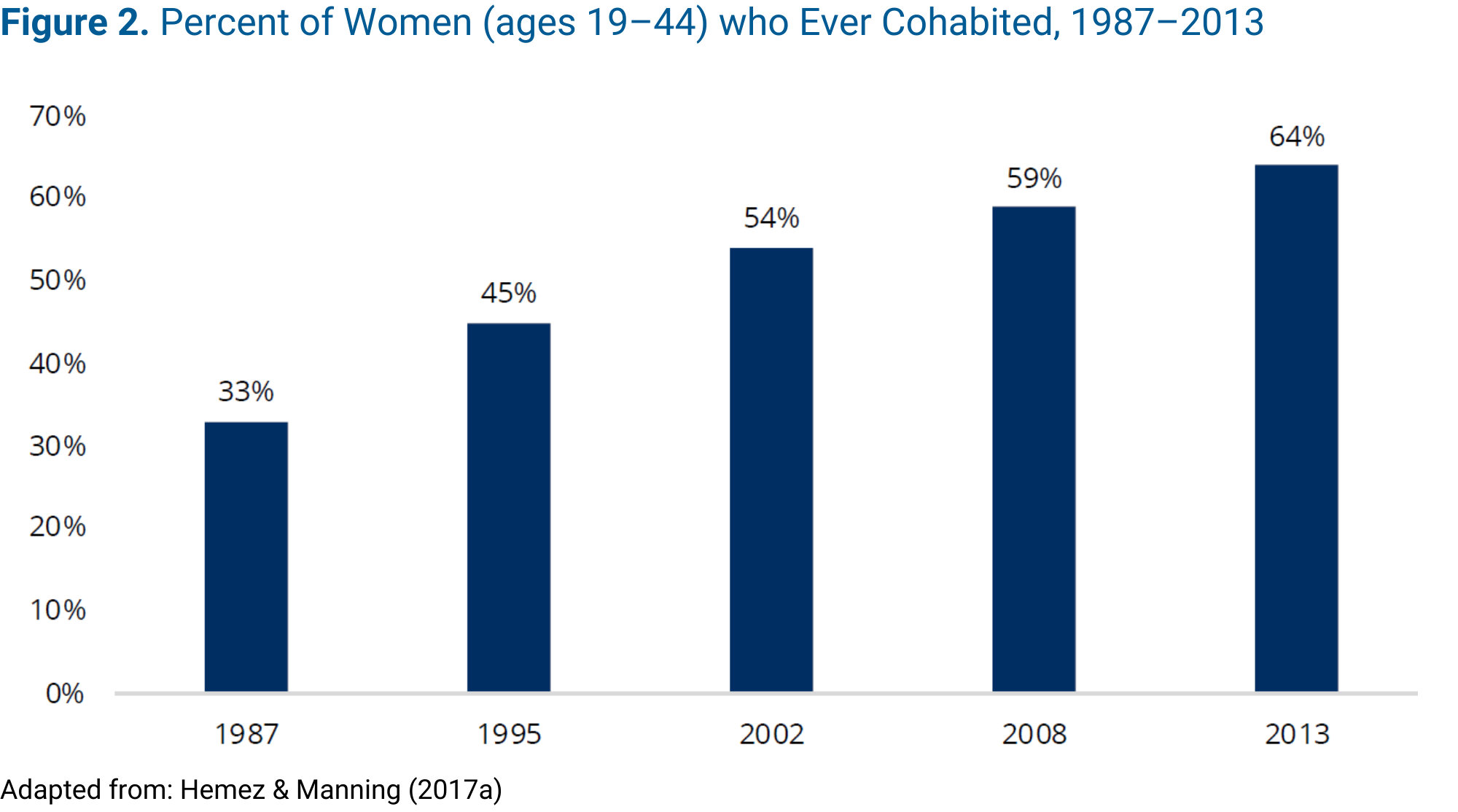

There are two ways to examine the prevalence of marriage: by measuring the proportion of individuals currently married or the proportion of individuals who have ever been married (i.e., formerly married persons). Since the middle of the last century, the prevalence of both has declined. In 1960, 65 percent of women (age 15 and older) were currently married; by 2016, however, this percentage had declined to 46 percent (Figure 3). 30 Similarly, from 1960 to 2010, the percentage of women who reported having ever been married declined from more than 80 percent to 73 percent. 31

After steadily increasing for the past several decades, the age at first marriage has reached a historic high. 32 The median age at first marriage in 2018 was 29.8 for men and 27.8 for women, compared to a median age of 23.2 for men and 20.8 for women in 1970. 32

As the age at first marriage has risen, the proportion of young people under the age of 24 who are married has declined. In 1968, 39 percent of young adults ages 18 to 24 lived with a spouse, compared to 7 percent in 2018. 33 The share of young people in “early marriages” (i.e., marriages in which both spouses are younger than age 25) has also declined over the past several years: 14 percent of marriages in 2008 were early marriages compared to 11 percent in 2015. 34

The marriage rate is a commonly used statistic that assesses the population-level tendency to marry at a particular point in time. Specifically, it measures the number of individuals who got married in a given year per 1,000 unmarried persons. The marriage rate is often calculated separately by gender, with most research tracking trends in women’s marriage rate by specific age groups. It can also be calculated across all marriages or for first marriages.

Between 1970 and 2010, the marriage rate for all marriages steadily declined, from 76.5 to 31.9 marriages per 1,000 unmarried women. Since 2010, the marriage rate has remained stable, and in 2017, there were 32.2 marriages for every 1,000 unmarried women. 35

Women’s first marriage patterns have also shifted dramatically in a parallel fashion. The rate of first marriage fell from 57.7 marriages per 1,000 never married women in 1990 to 41.5 marriages per 1,000 never married women in 2017. 36 Importantly, it is women’s older age at first marriage that underlies the observed decline in first marriage rates. Women over the age of 30, for example, have actually experienced an increase in their first marriage rate over the past 20 years, whereas women under the age of 25 have experienced a decline. 36

Most Americans have been married once, but a substantial minority of men and women have been married more than once. Overall, the remarriage rate declined from 50 remarriages per 1,000 previously married men and women in 1960 to 28 remarriages per 1,000 previously married men and women in 2016. 37-39 In 2013, 20 percent of marriages were a remarriage for one spouse, and 20 percent were a remarriage for both spouses. 40

Understanding trends in marital dissolution has important implications for the well-being of family members. Men and women who divorce, for example, often experience more financial insecurity, poorer health and well-being, and more depressive symptoms than those in stable marriages. 41 Likewise, children whose parents end their marriage also tend to experience poorer educational outcomes and higher levels of anxiety and depression than children living with parents who did not divorce. 42

Drawing from existing resources, we summarize data on estimates and trends on the following aspects of marital dissolution: 1) the prevalence of divorce, 2) the average age at divorce, 3) the divorce rate, and 4) marital duration at divorce.

Research on the dissolution of marriages focuses on divorce and/or separation. Divorce is defined as the legal termination of a marriage, whereas separation refers to the formal or informal decoupling of spouses into different households. 31 A complication for studying marital dissolution is that not all couples who separate subsequently divorce, and some even get back together. For instance, among couples who married by 2006, slightly over one-tenth of those who separated reconciled within five years. 43 Most of the time, however, separations eventually transition to divorce: More than half of separations ended in divorce within three years, and nearly two-thirds of separated couples had divorced within five years of the separation. 43

Research on divorce trends relies on a variety of data sources; these include the American Community Survey, the Current Population Survey, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, and the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Because men and women must first be married before becoming divorced or separated, estimates of marital dissolution are limited to currently or ever married individuals. In this brief, we generally focus on trends in divorce rather than separation. Separation is harder to measure than divorce since reporting requirements and definitions for separation vary by state. Additionally, separation can occur either informally (with couples deciding to live in separate residences) or formally (with a court-recognized agreement about managing affairs and assets while living apart), further impeding identification of separated couples.

Despite the common perception that half of marriages will end in divorce, prior literature suggests that, at the end of the 20th century, there was 43 to 46 percent chance that a marriage would end in divorce. 42 Furthermore, the risk of dissolution has changed over time. From 1950 to 1990, the chances that a marriage would end in divorce increased from 29 percent to 45 percent, after which the risk of divorce has remained stable. 44

Another way to assess divorce is to move beyond the couple-level estimates and consider the share of the ever-married population that has experienced a divorce. Estimates suggest that in 1970, roughly 13 percent of ever-married men and women had divorced or separated by ages 60 to 64. 45 By 2010, nearly half of ever-married men and women had been divorced or separated by these ages. 45

From 1970 to 2015, the median age at first divorce increased from 30.5 to 41.2 for men and from 27.7 to 39.7 for women, with the median age at first divorce consistently being one to two years older for men than for women. 46

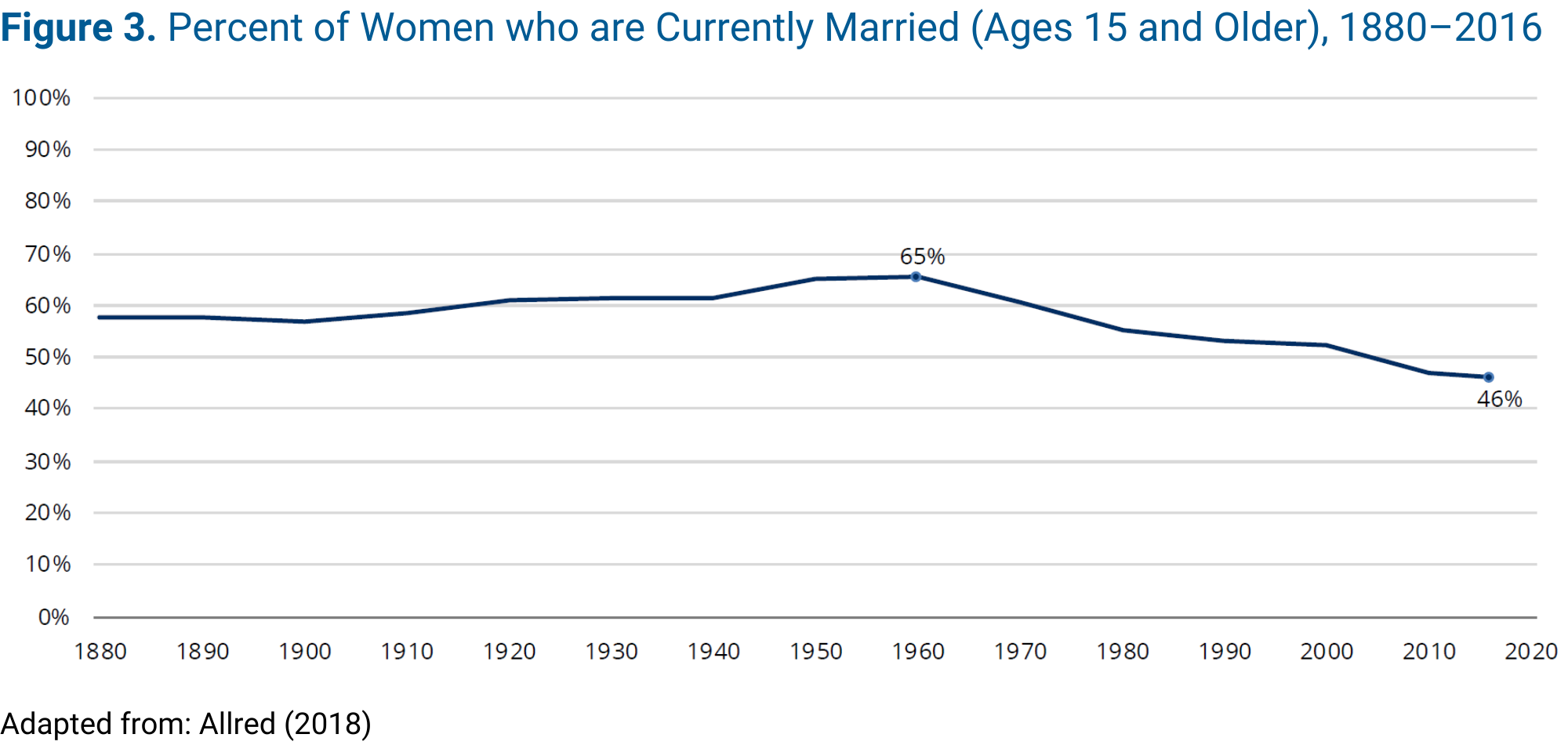

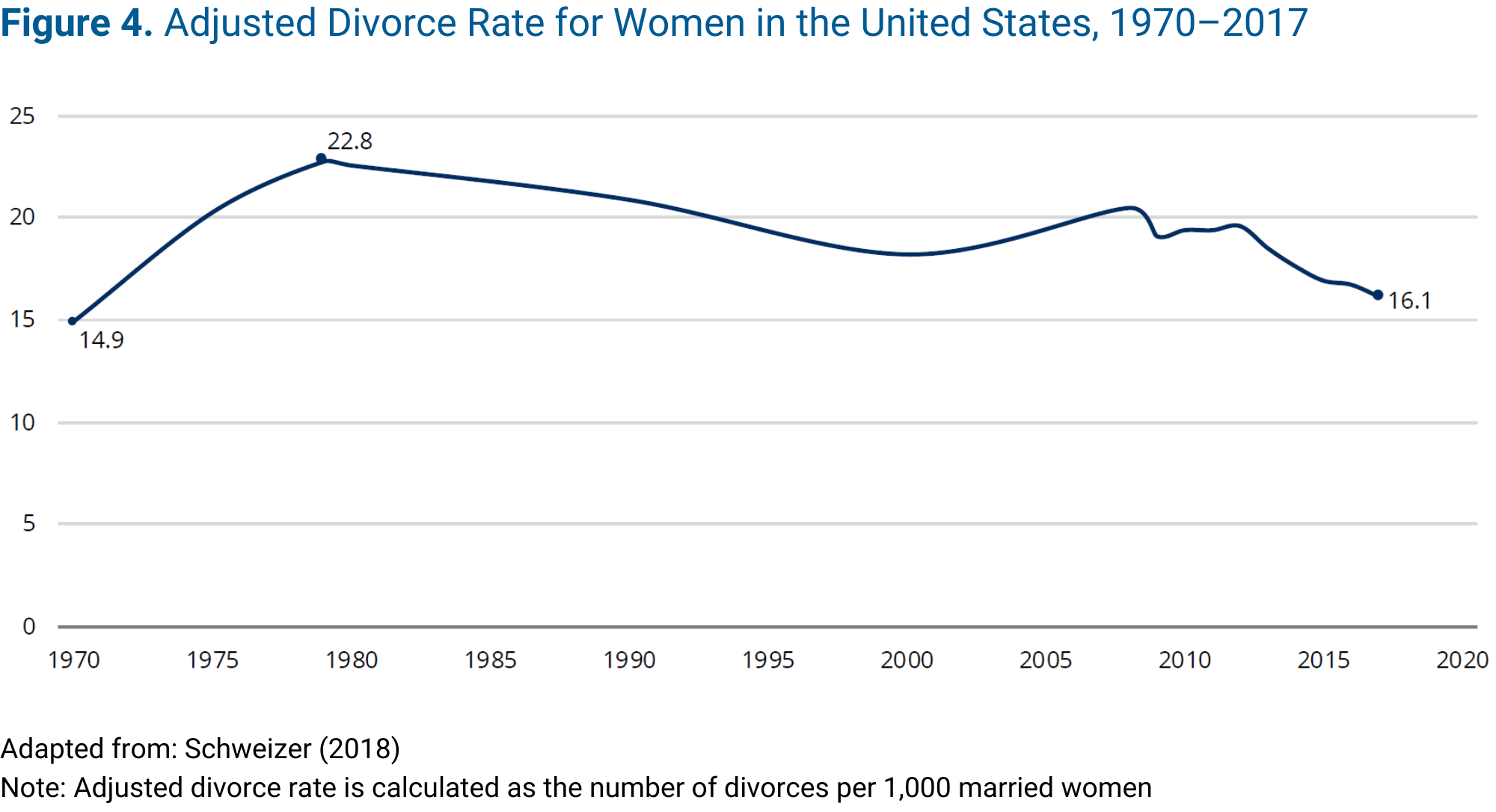

Figure 4 shows changes in the divorce rate for women in the United States over time (number of divorces per 1,000 married women). The divorce rate increased steadily from 14.9 divorces per 1,000 married women in 1970 to a peak of 22.8 in 1979. 47 Except for a slight upturn in the early 2000s, the divorce rate has generally declined since 1979, and it is currently the lowest it has been in nearly 50 years. In 2017, the divorce rate was 16.1, representing roughly one million women experiencing a divorce in that year. 47 The decline in the divorce rate is similar for both men and women. 48

The overall decrease in divorce rates in recent years masks differences in the trends by age: Among younger people, divorce is dropping steeply, but among older people it is increasing. The divorce rate among those over the age of 35, for example, has doubled over the past 20 years, despite the risk of divorce diminishing with age. 45, 49 Meanwhile, the steepest decline in the divorce rate has occurred for the youngest married women and men (ages 15–24): Their divorce rate dropped nearly 40 percent since 1990. 48

While divorce rates have declined, there has been little change in the length of time that couples have been married prior to divorce. The median duration of marriages that ended in 2012, for example, was 12.3 years, a duration that has remained relatively stable in recent years. 50, 51

However, in examining marital duration as the share of marriages that reach certain anniversaries, it appears that marriages formed in the late 20th century are not lasting as long as marriages formed in the mid-20th century. Evidence based on the 2009 Survey of Income and Program Participation, a nationally representative household based survey of adults 15 and older, indicates that two-thirds (67 percent) of women who married from 1960 to 1964 reached their twentieth anniversary (in 1980 to 1984), whereas just 57 percent of women who married from 1980 to 1984 were still married in 2000 to 2004. 52

This review of research on relationship formation and dissolution trends reveals several key implications about the changing context of relationship formation, the ways in which relationships are defined and measured in national surveys, and the understudied populations in the relationship formation literature that future research should consider.

First, more research is needed to understand the changing context of relationship formation. In addition to the changing patterns of romantic relationship formation and dissolution detailed in this brief, the circumstances under which formation and dissolution occur are also changing. For example, a recent exploration of how couples meet shows that the internet is now the most common avenue for relationship formation. 11 The expansion of internet dating websites and applications creates new ways for men and women to meet prospective partners, providing greater opportunities to form relationships; however, it also potentially introduces new challenges (e.g., differences in social networks and backgrounds) that could impact relationship quality and stability. An important topic for future research is to determine whether (and how) pathways to meeting romantic partners, including internet dating, are linked to relationship progression and outcomes.

Second, researchers should pay close attention to how relationships are defined and measured. As detailed in this brief, the nature of romantic relationships is changing across generations and over time. However, the ways that these relationships are actually defined and measured in our commonly used data sets may influence the patterns we see. For example, one explanation for the reductions in the shares of adolescents who date is the changes in the terms used to describe these relationships across generations. 7 Using the term “date/dating” in a questionnaire about relationship status may capture the experiences of mid- and later-life adults, whereas adolescents may refer to these relationships as “hanging out.” Likewise, some studies find that differences in the wording of questions about cohabitation can result in varying estimates of the prevalence of this relationship. 18

It is therefore important for researchers to recognize that the labels given to these relationships are socially constructed and can change over time; in addition, by identifying current definitions and jargon surrounding relationships and incorporating them into surveys, researchers can ask questions that better capture the experiences of specific populations. Measurement challenges are more likely to influence the estimates of less formal union types (e.g. dating, cohabitation, separation) than those of formal events (marriage and divorce). However, changes in the norms and meaning of marriage suggest that future research should also acknowledge that the institution of marriage has not remained constant throughout the past century.

Third, because there is only limited existing research on the relationships of same-gender couples, we could not include these types of relationships in our discussion of trends over time. However, since the legalization of same-gender marriage in 2015, this area of research has been rapidly growing. Future work examining trends in the formation/dissolution of dating, cohabiting, and marital relationships among same-gender couples—perhaps in comparison to different-gender couples—could provide key insights into the shifting patterns of relationship formation and stability in the United States as a whole.

Programmatic efforts to strengthen the quality and stability of couples’ relationships through healthy marriage and relationship education (HMRE) must be responsive to the changing nature of romantic relationship formation in the United States. Although these programs are often aimed at unmarried parents, the trends in dating, cohabitation, marriage, and divorce examined in this brief suggest several windows of opportunity for more comprehensive programming.

First, the declining percentage of adolescents who report dating during high school suggests a growing opportunity for programs to reach adolescents prior to romantic involvements. A range of HMRE curricula and programs for youth exist, and an increasing number of federally funded programs focus on serving youth ages 14 to 24. 53 However, more research on the design, implementation, and effectiveness of HMRE programs specifically for youth is needed, especially programs that use terminology that corresponds to the ways that teens and young adults view their romantic experiences.

Second, the high levels of cohabitation experienced across the young adult life course signal the importance of moving beyond a focus on marriage to considering the unique features of cohabiting relationships and helping to ensure that they are healthy. Given that many young adults cohabit at some point during their twenties, relationship education programs should address the age-specific difficulties young adults may face in their cohabiting relationships such as debt and financial insecurity. Many HMRE programs focus on improving the relationships of vulnerable populations (low-income couples), but programs should be designed more broadly to promote healthy unions across various types of relationships.

Third, HMRE programs may want to incorporate a focus on the unique stresses experienced by couples when one or both partners have had prior cohabitations or marriages, given that the share of couples with such prior relationships is growing. As a starting point, several resources have been developed to support practitioners in providing tailored services to both married and unmarried parents and their children in blended families. 54 These resources should be further developed to consider how prior relationship experiences—and the family ties resulting from these relationships, such as children, former partners, and the like—affect well-being and the functioning of the current relationship. For example, these programs could consider how relationships involving one previously married partner differ from those where both partners are previously married. By considering relationship-specific characteristics, education programs can provide services that are better suited to serve individuals and couples in particular types of relationships.

Fourth, assessments of HMRE program success should not be measured exclusively by increases in marriage or decreases in divorce at the aggregate level (i.e., national or state). Rather, evaluations of program impact should recognize the broader context of marriage and divorce, including overall trends, to understand the influence that these programs have on relationships. For instance, reductions in the divorce rates of program participants should not be interpreted as support for the success of HMRE programs if divorce rates for the geographic area on the whole are also declining.

Fifth, though programs should certainly track whether participants marry, or at least stay together (and whether they do so at a higher rate than those in a control group or an otherwise similar population), the success of HMRE programs should also be measured in other ways. For instance, programs can conduct evaluations of both positive and negative aspects of relationship quality before and after couples experience the program. Similarly, they can conduct self-evaluations of whether respondents feel their relationship improved as a direct result of program participation. Future briefs in this series will provide an overview of key relationship quality measures identified in relationship research, as well as describe how relationship quality is incorporated and evaluated in programmatic efforts.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that relationship stability is not necessarily the best outcome for all couples or individuals. There are relationships in which violence or infidelity are ongoing issues. Some individuals are partnered with those unwilling or unable to make necessary positive changes; staying with a partner with a serious overspending or gambling habit, for instance, or a major addiction, can reduce well-being over the long term. 55, 56 In these scenarios, it may be healthiest for relationships to end. Programs need a way to identify relationships that perhaps should not be maintained and the ability to pivot to support dissolution in a way that is safe and productive for both partners.

This brief is based on a comprehensive review of professional and scientific journal articles or book chapters published in or after 2010. Generally, the data used by empirical research cited in this brief are nationally representative surveys (listed to the right).

Although the descriptions of relationship trends in this brief are not restricted to a particular time period, estimates are limited to the available research/data. Therefore, the periods examined may not be consistent throughout the brief, although the trends presented generally cover at least a 25-year period and end during the 2010s.