The Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, passed in December 2019, brought a wide range of changes to the retirement planning landscape, from the death of the ‘stretch’ IRA to raising the age for Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) to 72. And nearly 3 years to the day after its predecessor was passed, the U.S. House of Representatives, on December 23, 2022, passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, an omnibus spending bill that includes the much-anticipated and long-awaited retirement bill known as SECURE Act 2.0.

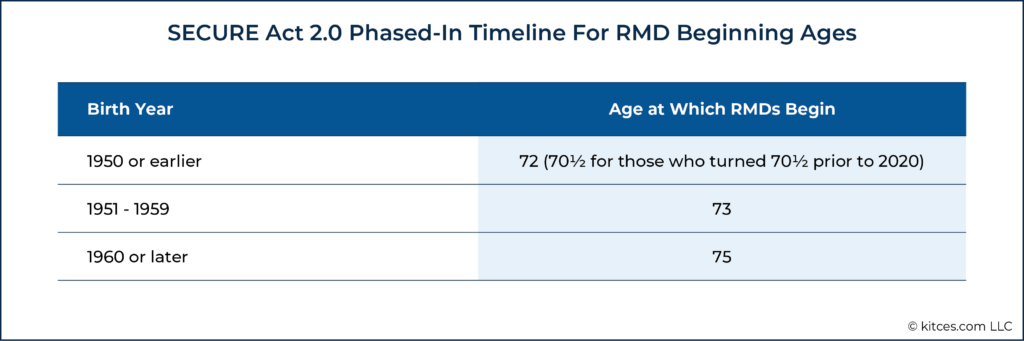

One of the major headline changes from the original SECURE Act was raising the age for RMDs from 70 ½ to 72, and SECURE 2.0 pushes this out further to age 73 for individuals born between 1951 and 1959 and age 75 for those born in 1960 or later. In addition, the bill decreases the penalty for missed RMDs (or distributing too little) from 50% to 25% of the shortfall, and if the mistake is corrected in a timely manner, the penalty is reduced to 10%.

In addition, SECURE 2.0 includes a significant number of Roth-related changes (both involving Roth IRAs as well as Roth accounts in employer retirement plans), though notably, the legislation does not include any provisions that restrict or eliminate existing Roth strategies (e.g., backdoor Roth conversions). These changes include aligning the rules for employer-retirement-plan-based Roth accounts (e.g., Roth 401(k) and Roth 403(b) plans) with those for individual Roth IRAs by eliminating RMDs, creating a Roth-style version of SEP and SIMPLE IRA accounts, allowing employers to make matching contributions and non-elective contributions to the Roth side of the retirement plan instead of just the pre-tax portion (though participants will be subject to income tax on such contributions), and allowing for transfers from 529 plans to Roth IRAs (with significant restrictions).

SECURE 2.0 also includes several measures meant to encourage increased retirement savings. These include making IRA catch-up contributions subject to COLAs beginning in 2024 (so that they will increase with inflation from the current $1,000 limit), while also increasing 401(k) and similar plan catch-up contributions; creating a new “Starter 401(k)” plan (aimed at small businesses that do not currently offer retirement plans; such plans would include default auto-enrollment and contribution limits equal to the IRA contribution limits, among other features); and treating student loan payments as elective deferrals for employer matching purposes in workplace retirement accounts, which would allow student loan borrowers to benefit from an employer match even if they can't afford to contribute to their own retirement plan.

Ultimately, the key point is that while no single change in SECURE 2.0 will require the same level of urgency to consider before year-end changes to clients’ plans as did the original SECURE Act or have the same level of impact across so many clients’ plans as the elimination of the stretch, there are far more provisions in SECURE 2.0 that may have a significant impact for some clients than there were in the original version, making it a more challenging bill for financial advisors and other professionals to contend with (yet providing many new potential opportunities)!

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, AIF, CWS, MSA is the Lead Financial Planning Nerd for Kitces.com, a leading online resource for financial planning professionals, and also serves as the Chief Planning Officer for Buckingham Strategic Wealth. In 2020, Jeffrey was named to Investment Advisor Magazine’s IA25, as one of the top 25 voices to turn to during uncertain times. Also in 2020, Jeffrey was named by Financial Advisor Magazine as a Young Advisor to Watch. Jeffrey is a recipient of the Standing Ovation award, presented by the AICPA Financial Planning Division for “exemplary professional achievement in personal financial planning services.” He was also named to the 2017 class of 40 Under 40 by InvestmentNews, which recognizes “accomplishment, contribution to the financial advice industry, leadership and promise for the future.” Jeffrey is the Creator and Program Leader for Savvy IRA Planning®, as well as the Co-Creator and Co-Program Leader for Savvy Tax Planning®, both offered through Horsesmouth, LLC. He is a regular contributor to Forbes.com, as well as numerous industry publications, and is commonly sought after by journalists for his insights. You can follow Jeff on Twitter @CPAPlanner.

Read more of Jeff’s articles Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, an omnibus spending bill authorizing roughly $1.7 trillion in new Federal spending. Included in the monstrous 4,000+ page document was the much-anticipated and long-awaited retirement bill known as SECURE Act 2.0.

SECURE Act 2.0 arrives nearly 3 years to the day after its predecessor, the original SECURE Act, was passed in late 2019. Amongst other changes, the first bill included the massively impactful provision that eliminated the 'stretch' IRA option for most non-spouse beneficiaries of retirement plans.

It’s probably fair to say that no single change made by SECURE Act 2.0 will have the same level of impact across so many clients’ plans as the elimination of the stretch, as retirement accounts were now required to be fully distributed within 10 years of the original account holder’s death, rather than withdrawals being spread out gradually over the beneficiary’s lifetime. Likewise, no change made by SECURE Act 2.0 creates the same level of urgency to consider nearly immediate changes to clients’ plans before year-end as did the original SECURE Act. But that’s not to say that the provisions of SECURE Act 2.0 are either insignificant or small.

In fact, there are far more provisions in SECURE Act 2.0 that may have a significant impact on some clients than there were in the original version. The sheer volume of changes, combined with their more targeted impact, have the potential to make SECURE Act 2.0 a more challenging bill for financial advisors and other professionals to contend with.

The following is a 'brief' outline of some of the provisions of SECURE Act 2.0 that are most likely to impact clients – both now and in the years to come.

When the Tax Reform Act of 1986 first established Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from qualified retirement accounts, it set the date when RMDs were required to begin as the year in which an individual reached age 70 ½. That remained the necessary age for RMDs for more than 30 years until 2019, when the original SECURE Act moved it to age 72 starting in 2020 (for those turning 70 ½ or older in 2020 or later).

Now, just 3 years later, Section 107 of SECURE Act 2.0 further pushes back the age at which RMDs must begin. More specifically, the law states:

In the case of an individual who attains age 72 after December 31, 2022, and age 73 before January 1, 2033, the applicable age is 73.

The law continues on to say:

In the case of an individual who attains age 74 after December 31, 2032, the applicable age is 75.

Thus, for individuals who turn 72 in 2023, RMDs will be pushed back by 1 year compared to the current rules and will begin at age 73. Age 73 will continue to be the age at which RMDs begin through 2032. Then, beginning in 2033, RMDs will be pushed back further, to age 75.

Those reading the language from SECURE Act 2.0 above closely (you are reading closely, aren’t you?) may have noticed a bit of an issue. Notably, the first excerpt states that the new age 73 applicable age will apply to those who turn “age 73 before January 1, 2033.” Thus, individuals born in 1959, who turn 73 in 2032 (i.e., before 2033) would fall into this category.

The second excerpt, however, says that the new applicable age of 75 will apply to those who turn “74 after December 31, 2032.” The problem here is that an individual born in 1959 turns 74 in 2033 (i.e., after December 31, 2032). Thus, individuals born in 1959 would appear to have 2 ages – 74 and 75 – at which they are supposed to begin RMDs!

Clearly, that’s not possible, and it’s most likely that the double RMD date represents a drafting error in the text of the legislation. Indeed, in the days since the bill tax was released, I have spoken with multiple parties who have confirmed that both the discrepancy is a drafting error, and the intention is for the age 75 applicable age to apply to those turning 75 in 2033 or later (and thus, to those who turn 74 after December 31, 2033, not December 31, 2032). In other words, the intention of the law is that a person born in 1959 should begin RMDs at age 73, not 75.

A technical correction is likely to be included in another bill in the near future, but in reality, there’s no rush to do so as Congress has nearly a decade to fix the issue before it becomes a true problem.

The following table summarizes the ages at which RMDs are generally required to begin under SECURE Act 2.0:

Many of the same questions that arose after the original SECURE Act’s change of the RMD age are likely to arise again. To that end, it’s helpful for advisors to have answers to the following:

Q: If I was supposed to begin my RMDs this year, do I still need to?

A: In general, yes. The changes do not impact individuals turning 72 in 2022 (or earlier years), who would have needed to begin (or continue) RMDs in 2022. Thus, in general individuals turning 72 this year (2022) must still take their first RMD by April 1, 2023.

Q: What other financial planning considerations are tied to the RMD age that will be impacted by this change?

A: The changes to the RMD age made by SECURE Act 2.0 also impact the age at which the following provisions apply:

Q: Does SECURE 2.0 also push back the date when I can begin Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) from an IRA?

A: No. The changes to the RMD age made by SECURE Act 2.0 do not impact the age at which Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) can be made. Individuals can still make QCDs starting at age 70 ½.

It’s also worth noting that as a result of the change, the year 2023 will represent an oddity of sorts, in that no retirement account owners will be required to begin taking RMDs in 2023 because of their age.

Example 1: Tweedledee and Tweedledum are twins. Tweedledee was born at 11:58PM on December 31, 1950, and therefore turns 72 on December 31, 2022. Accordingly, he must begin taking RMDs in the year he turns 72, which is 2022.

Tweedledum was born 5 minutes later, at 12:03am on January 1, 1951. She, therefore, turns 72 on January 1, 2023 (after 2022). Per the new rules of the SECURE 2.0 Act, she must begin taking RMDs in the year she turns 73, which is 2024.

Note that neither of them begins taking RMDs in 2023!

Ultimately, pushing back the age for RMDs is a neutral-to-positive change for most clients. For individuals who already need to take distributions beyond their RMD level to support living expenses, the change is largely irrelevant. For some clients, however, the change will be viewed as welcome news, as it may allow them to push off retirement-account income for a few more years in an effort to stave off higher Medicare Part B/D premiums and, perhaps, to have a few more years of tax-efficient Roth conversions. Advisors should work closely with affected clients to determine the optimal approach.

SECURE Act 2.0 includes a significant number of Roth-related changes (both involving Roth IRAs as well as Roth account in employer retirement plans). Importantly, all of these changes should be neutral-to-good news for clients in terms of the planning considerations and opportunities created.

To that end, SECURE Act 2.0 does not include any provisions that restrict or eliminate existing Roth strategies. To the contrary, the changes highlight Congress’s continued march toward ‘Rothification’, perhaps in an effort to grab tax revenue now in order to make Federal budget estimates look better (or at least less bad).

Effective in 2024, Sec. 325 of SECURE Act 2.0 eliminates RMDs for Roth accounts in qualified employer plans beginning in 2024. Currently, while Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs during the owner’s lifetime, employer plan Roth accounts, such as Roth 401(k) plans, Roth 403(b) plans, governmental Roth 457(b) plans, and the Roth component of the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, are subject to the regular RMD rules, making them subject to RMDs beginning at age 72 (although such distributions are tax-free per the standard rules for Roth account withdrawals).

Clearly, it would never make sense to take money out of Roth accounts that would otherwise grow tax-free unless they were truly needed. Accordingly, because of the disparity between the rules for Roth accounts in qualified employer plans with RMDs (that will continue to be required until 2024) and Roth IRAs with no RMDs, rolling over plan Roth account assets into a Roth IRA has historically been a near no-brainer for most individuals. Naturally, this has upset providers of employer-sponsored retirement plans (who often earn their fees in the form of a percentage of assets in the plan), since the difference in the rules created an unfair advantage for IRA providers and proved to be a major source of plan leakage.

Now, as a result of SECURE Act 2.0, plan Roth accounts and Roth IRAs will be on more of a level playing field. Accordingly, it won’t be quite so obvious to determine whether or not rolling over a plan Roth account to a Roth IRA is in the client’s best interest going forward. Instead, the decision may have to be based on factors similar to those used by advisors to determine whether or not to roll over a (pre-tax) plan into a traditional IRA.

Notably, the language of SECURE Act 2.0 appears to flat-out eliminate RMDs from plan Roth accounts beginning in 2024, rather than merely eliminating them only for those who would have needed to begin taking RMDs after the change is effective. Thus, those individuals with plan Roth accounts who have already been taking RMDs from those accounts should simply be able to stop taking them beginning in 2024.

The fact that this change is made during the Biden administration is particularly interesting given that it represents a complete 180 from the proposal to align Roth IRA and plan Roth rules under the Obama administration (during which President Biden served as Vice President). Namely, on several occasions, President Obama’s budget requests included provisions that would have aligned the 2 accounts’ rules by adding RMDs to Roth IRAs (rather than the ultimate solution arrived at in SECURE Act 2.0 of eliminating them for plan Roth accounts instead).

Beginning just a few days from now, taxpayers will have 2 new opportunities for Roth contributions. More specifically, Sec. 601 of SECURE Act 2.0 authorizes the creation of both SIMPLE Roth accounts, as well as SEP Roth IRAs, for 2023 and beyond. Previously, SIMPLE and SEP plans could only include pre-tax funds.

Notably, although individuals technically have the legal ability to create and contribute to Roth SIMPLE and SEP IRA accounts beginning January 1, 2023, it will likely take at least some time before employers, custodians, and the IRS are able to implement the procedures and policies necessary to actually effectuate such contributions. Specifically, SECURE Act 2.0 only authorizes the use of SIMPLE and SEP Roth IRAs after an election has been made to do so, and that such election must be in a manner approved by the IRS.

Ultimately, this shouldn’t be that complicated, as similar requirements already exist for the designation of Roth deferrals into 401(k) and similar plans. Nevertheless, the IRS must still formally approve what constitutes an “election”, custodians will have to update documents and procedures, and employers will have to educate plan participants about any new options they may have.

To the extent that a Roth election is made and amounts are deposited into a SIMPLE Roth IRA or SEP Roth IRA, the amounts contributed will be included in the taxpayer’s income.

Ultimately, the creation of SIMPLE Roth IRAs and SEP Roth IRAs does more to create the potential for operational efficiency than it does to actually bring to life new planning opportunities. Individuals who receive SEP contributions have long had the opportunity to immediately convert those dollars to a Roth IRA if they so chose. Similarly, SIMPLE IRA participants are able to make such Roth conversions after the SIMPLE IRA has been funded (with the first dollars) for at least 2 years.

Section 604 of SECURE Act 2.0 continues the theme of expanding available options for getting money into Roth accounts. More specifically, effective upon enactment, employers will be permitted to deposit matching and/or nonelective contributions to employees’ designated Roth accounts (e.g., Roth accounts in 401(k) and 403(b) plans). Such amounts will be included in the employee’s income in the year of contribution, and must be nonforfeitable (i.e., not subject to a vesting schedule).

Notably, while SECURE Act 2.0 authorizes such contributions immediately upon enactment, employers and plan administrators will need time to update systems, paperwork, and procedures to accommodate the change. As such, it may take some time before employers actually have the ability to direct contributions in such a manner.

As discussed above, SECURE Act 2.0 gives taxpayers more options with respect to the traditional versus Roth decision in some areas. In other areas, though, the bill takes that same decision out of the taxpayer’s hands.

Section 603 of SECURE Act 2.0 creates a mandatory 'Rothification’ of catch-up contributions for certain high-income taxpayers starting in 2024 (likely in an effort to increase revenue to help pay for other parts of the legislation). The new rule applies to catch-up contributions for 401(k), 403(b), and governmental 457(b) plans, but not to catch-up contributions for IRAs, including SIMPLE IRAs.

The precise language of the provision, however, appears to create a number of quirks that could result in unintended consequences and/or planning opportunities for some individuals.

From SECURE Act 2.0, Section 603:

(A) IN GENERAL.— Except as provided in subparagraph (C), in the case of an eligible participant whose wages (as defined in section 3121(a)) for the preceding calendar year from the employer sponsoring the plan exceed $145,000, paragraph (1) shall apply only if any additional elective deferrals are designated Roth contributions (as defined in section 402A(c)(1)) made pursuant to an employee election. [Emphasis added]

To begin with, note that the Roth restriction on catch-up contributions imposed by SECURE Act 2.0 only applies to those who have wages in excess of $145,000 (which will be adjusted for inflation in the future) in the previous calendar year. Thus, it would appear that self-employed individuals (e.g., sole proprietors and partners) would continue to have the opportunity to make pre-tax catch-up contributions, even if their income from self-employment is higher than $145,000.

While it may seem unfair for the catch-up provision to treat high-income wage earners differently from equally high-earning self-employed individuals, the disparity is likely due to the irrevocable nature of plan Roth deferrals. Specifically, there is no mechanism to retroactively change plan Roth deferrals into pre-tax plan deferrals if the taxpayer’s wages turned out to be too high (compared with Roth IRA contributions, which can be recharacterized as traditional IRA contributions if the individual’s income exceeds the Roth IRA contribution limits). And whereas a wage earner will generally know their exact wages for the previous year (which dictates whether or not their catch-up contributions must be Roth) by the first paycheck of a new year, a self-employed individual may not know their net income from self-employment until their tax return is filed – meaning they may go several months into the new year without knowing which types of catch-up contribution they are allowed to make and having no way to undo any contributions they’ve already made.

Additionally, note that the Rothification restriction language above refers to wages paid in “the preceding calendar year from the employer sponsoring the plan”. Thus, it would appear that if an individual is 50 years old or older and changes employers, they may be eligible to make pre-tax catch-up contributions to the new employer’s plan for 1, or possibly even 2 years, even if their combined wages from both employers in each of those years exceeds $145,000, as long as the amount earned from just their current employer doesn’t exceed that number.

Example 2: Alice is a 55-year-old advertising executive earning wages of $200,000 per year. Based on her current salary, she would be unable to make a pre-tax catch-up contribution to her employer’s 401(k) plan beginning in 2024.

Suppose, however, that early in 2024, Alice is offered a job by a competing advertising company, and they agree to pay her an annualized salary of $250,000. Further suppose that Alice accepts the offer, and begins employment at the new ad agency on July 1, 2024.

Alice’s total wages for 2023 will have been $200,000, well in excess of the $145,000 cap set by Section 603 of SECURE Act 2.0. However, those wages would have been earned from a previous employer. Once Alice switches employers mid-year, she’ll be able to make pre-tax contributions to the new employer’s plan (assuming she was otherwise eligible for participation in the plan), because she didn’t earn any wages from them in the previous year.

Furthermore, while Alice will have earned a total of (½ year × $200,000 salary) + (½ year × $250,000 salary) = $225,000 of wages in 2024, only ½ year × $250,000 = $125,000 will have been earned from her new employer. Thus, in 2025, Alice would be able to answer “no” to the question, “Did you receive more than $145,000 in wages from the employer sponsoring your plan in the previous year?” Accordingly, she would continue to be eligible for pre-tax catch-up contributions to the new employer’s 401(k) plan in 2025, and would not have to make those catch-up contributions to a Roth account.

It’s worth noting that while 401(k) and similar plans can include a Roth component, they are not required to do so. Of course, that raises the obvious question, “What happens when employees who are required to make Roth catch-up contributions (i.e., those whose previous-year wages exceeded $145,000) are unable to do because their employers don’t have a Roth option?”

SECURE Act 2.0 addresses this possibility head-on. In short, the law says that if the plan does not allow individuals to make catch-up contributions to a Roth account, the catch-up contribution rules will not apply to that plan (for both those with wages above and below the applicable $145,000 threshold). In other words, if an employer's plan includes employees eligible to make catch-up contributions and who earned over $145,000 in the previous year, but if the plan didn't include a Roth catch-up contribution option, then no one would be allowed to make catch-up contributions, regardless of their previous-year wages.

One of the provisions of SECURE Act 2.0 that has grabbed a disproportionate percentage of headlines in financial media is the introduction of the ability, beginning in 2024, for some individuals to move 529 plan money directly into a Roth IRA. This new transfer pathway, created by Section 126 of SECURE Act 2.0, will be an intriguing option for some individuals, but it also comes with a number of conditions that must be satisfied for the transfer to be valid and that limit the ability to take advantage of (or abuse) the provision. The conditions include:

Example 3: Helena is the beneficiary of a 529 plan account that has excess funds she will not need for school, and the account has been open for more than 15 years.

In 2024, Helena contributes $4,000 of her own earned income to a Roth IRA. As such, assuming the IRA contribution limit for 2024 remains at the $6,500 limit for 2023, the owner of Helena’s 529 plan could transfer up to another $6,500 - $4,000 = $2,500 into her Roth IRA for the year.

The legislative text of this provision leaves a lot to be desired. For instance, it’s not entirely clear whether a change in the 529 plan’s beneficiary will trigger a new 15-year 'seasoning' period before those funds can be transferred to a Roth IRA. Initial indications from Congress seem to point to the 15-year period being unaffected by a change in a beneficiary, but written guidance from Congress or the IRS will be needed to confirm (or reject) that assumption. Such treatment would seem to make sense, though, if Congress is trying to nudge parents and other interested parties concerned about the “What if they don’t go to college?” question to make 529 plan contributions. For instance, if a parent contributed to a 529 plan account for the benefit of their child (and maintained ownership of the account) but the child did not need nor use the 529 plan money, it appears that the parent would be able to change the beneficiary to themselves and transfer the 529 plan’s account value to their own Roth IRA (subject to the aforementioned restrictions).

While as described above, there are a number of restrictions on the ability to move 529 plan money to a Roth IRA, Section 126 of SECURE Act 2.0 also offers an advantage of 529 plan-to-Roth IRA transfers compared to ‘regular’ Roth IRA contributions. More specifically, individuals are generally prohibited from making regular Roth IRA contributions once their Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) exceeds an applicable threshold. Transfers of funds from 529 plans to Roth IRAs, authorized by SECURE Act 2.0, however, will not be subject to the same income limitations.

It is likely that most individuals will use the new ability to transfer up to $35,000 from a 529 plan to a Roth IRA (starting in 2024) for its congressionally intended purpose: allowing money that was earmarked for educational purposes to be repurposed as retirement savings in the event those funds are not needed for education after all. However, for a small cross-section of higher-net-worth families, this new technique could be used to 'prime the retirement pump' for children, grandchildren, and other loved ones.

For example, at the time a child is born, a meaningful contribution could be made to a 529 plan for their benefit. Later, after the child turns 16 (and the account has been in existence for over 15 years), the account’s funds could begin to be moved to a Roth IRA for the child’s benefit in the amount of the maximum IRA contribution amount for each year (although notably, the transfer rules require that the child have compensation - such as from a summer or part-time job - in order to make the transfer, such as would be required for them to make a 'regular' Roth IRA contribution). With proper planning and continued annual transfers until the $ 35,000 lifetime transfer limit is reached, the child’s Roth IRA balance at age 65 could easily approach, or even exceed, $1 million.

Under existing law, when a surviving spouse inherits a retirement account from a deceased spouse, they have a variety of options at their disposal that are not available to any other beneficiary (e.g., rolling the decedent’s IRA into their own, electing to treat the decedent’s IRA as their own, and remaining a beneficiary of the decedent’s IRA, but with special treatment). And beginning in 2024, Section 327 of SECURE Act 2.0 will extend the list of spouse-beneficiary-only options further by introducing the ability to elect to be treated as the deceased spouse.

Making such an election would provide the following benefits to the surviving spouse:

While Regulations will be needed to further flesh out details of this new option, at first glance, it would appear that its primary use case will be for surviving spouses who inherit retirement accounts from a younger spouse. By electing to treat themselves as the decedent, they will be able to delay RMDs longer, and once RMDs do start, they will be smaller than if the spouse had made a spousal rollover or remained a beneficiary of the account.

Example #4: The King of Hearts and the Queen of Hearts are a married couple. The King is 65 years old, while the Queen is 5 years his senior at 70 years old.

Unfortunately, during his weekly croquet match, the King was hit in the head with an errant croquet ball and died. Under current law, the Queen could roll over the King’s IRA into her own, but doing so would require her to begin RMDs in just a few short years (when she reaches her own RMD age). Alternatively, the Queen could choose to remain a beneficiary of the King’s IRA. Doing so would allow her to delay RMDs until the King would have reached RMD age, but once RMDs are required to begin, they would be based on her own (older) age.

By contrast, effective in 2024, section 327 of SECURE Act 2.0 would allow the Queen to elect to be treated as if she were the King. Thus, RMDs would be delayed for an additional 5 years, and once they are necessary, would be based on the King’s younger age (and thus smaller than if they were based on the Queen’s own age).

It’s worth noting that SECURE Act 2.0 states that once a surviving spouse has made the election to be treated as the deceased spouse, the election may not be “revoked except with the consent of the Secretary”. Exactly how one might go about revoking such an election, and what criteria the IRS may use to decide whether to authorize such a revocation, is something for which advisors and married couples will have to await future guidance.

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRA) of 2001 created IRA catch-up contributions, effective for 2002 and future years. Although that law, for the first time, indexed the annual IRA contribution limits to inflation, the catch-up contribution limit was introduced as a flat $500 amount that was not indexed.

In 2006, the Pension Protection Act doubled the original IRA catch-up contribution limit to a flat $1,000 but still failed to adjust that cap for inflation in future years. That was the last time Congress raised the limit manually and as such, the IRA catch-up contribution limit remains at the same $1,000 amount at which Congress set it more than 15 years ago.

Now, Section 108 of SECURE Act 2.0 will finally allow the IRA catch-up contribution limit to automatically adjust for inflation, effective starting in 2024. Inflation adjustments will be made in increments of $100, so get ready to keep track of the $1,200 IRA catch-up contribution limit in the not-too-distant future!

Prior to the passage of SECURE Act 2.0, the IRA catch-up contribution limit was the only annual retirement contribution limit that was not automatically indexed for inflation.

Effective for 2025 and in future years, Section 109 of SECURE Act 2.0 increases employer retirement plan (e.g., 401(k) and 403(b) plan) catch-up contribution limits for certain plan participants. More specifically, participants who are only ages 60, 61, 62, and 63 will have their plan catch-up contribution limit increased to the greater of $10,000, or 150% of the regular catch-up contribution amount (indexed for inflation) for such plans in 2024.

Similarly, SIMPLE Plan participants who are age 60, 61, 62, or 63 at year-end will have their plan catch-up contribution limit increased to the greater of $5,000 or 150% of the regular SIMPLE catch-up contribution amount for 2025 (indexed for inflation).

The language of the provision is a bit wonky, and there appears to be some confusion over the inclusion of the "greater of $10,000 or 150% of the future (regular) catch-up amount" when 150% of the 2023 catch-up amount is already going to be over $10,000 (as $7,500 x 150% = $11,250). Nevertheless, it's clear that beginning in a few years, the group of pre-retirees ages 60-63 will be able to stash away some additional amounts in their 401(k) or similar plan accounts, if they so choose.

Recall that Section 603 of SECURE Act 2.0 will require certain high-wage earners to make (non-SIMPLE) plan catch-up contributions only to Roth accounts beginning in 2024. Accordingly, in the following year (2025), when both the Rothification provision under Section 603 and the enhanced catch-up contribution limits under Section 109 are effective, some 60- to 63-year-old plan participants will find themselves able to make larger catch-up contributions – but only to the Roth side of their plan!

Since their introduction in 2006 as part of the Pension Protection Act, Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) have quickly become the best way for most individuals 70 ½ or older to satisfy their charitable intentions. The rules for these distributions, for which no charitable deduction is received because the income is excluded from AGI to begin with (which is much better, since such income is also excluded for the purposes of calculating the taxable amount of Social Security income and Medicare IRMAA surcharges, among other things), are modified by SECURE Act 2.0 in the following 2 ways:

At first glance, the ability to fund a CRUT, CRAT, or CGA with a QCD may seem like a significant benefit for some IRA owners, since it essentially allows them to remove funds from a traditional IRA tax-free to pass on to future generations free of income or estate tax. However, the reality is that there are a lot of strings attached to the provision that make it not quite the deal it may appear to be at first, especially for those interested in using their IRAs to fund a CRUT or CRAT.

For instance, the maximum amount that can be moved in this once-in-a-lifetime distribution is $50,000 (to be adjusted for inflation). It would be hard to imagine a scenario where it would be worth a taxpayer’s time and expense to set up a CRUT or CRAT for only $50,000.

No big deal you say? You’ll just throw the $50,000 IRA distribution into the client’s existing CRUT or CRAT? Not so fast, says Congress. Notably, Section 307 of SECURE 2.0 states that a distribution to a CRUT or CRAT will only count as a QCD “if such trust is funded exclusively by qualified charitable distributions”.

A further limitation says that the only income beneficiaries of such a qualifying CRUT or CRAT can be the IRA owner and their spouse. Accordingly, even if both spouses took full advantage of the one-time $50,000 QCD distribution to fund a split-interest entity, and they used those QCDs to fund the same CRUT or CRAT vehicle, the maximum contributions to the trust, in total, could be no more than $100,000. Again, it’s hard to imagine the time, expense, and complexity that comes along with creating and maintaining a CRUT or CRAT being worth it for such relatively modest contributions.

And if all of that wasn’t enough to convince you that QCD CRUTs/CRATs are unlikely to make sense for most clients, consider that whereas regular CRUTs and CRATs have the ability to invest in assets that generate long-term capital gains, qualified dividends, or other tax-preferenced income whose character is retained when distributed to beneficiaries, all such distributions from CRUTs and CRATs funded with QCDs will be classified as ordinary income!

As a result, for clients interested in utilizing the one-time ability to make a QCD of up to $50,000 to fund a split-interest entity, the entity of choice will likely be a Charitable Gift Annuity (CGA). Such entities are created and operated by charities, limiting the associated out-of-pocket costs for taxpayers. Notably, though, CGAs funded via QCDs would be subject to the additional requirements that payments begin no less than 1 year after funding, and such payments are established at a fixed rate of 5% or greater.

In general, Section 72 of the Internal Revenue Code imposes a 10% penalty for distributions from retirement accounts taken prior to reaching age 59 ½. The rationale is obvious. Congress is trying to discourage the use of retirement funds for something other than their stated purpose… retirement!

Nevertheless, historically, Congress has authorized a limited number of exceptions to the 10% penalty in the event taxpayers have certain expenses (e.g., higher education or deductible medical expenses) or experience certain events (e.g., death or disability) it deems as an acceptable excuse to dip into retirement savings earlier than is generally intended. In recent years, Congress has steadily sought to expand that list via various pieces of legislation, such as the original SECURE Act, the CARES Act, and others.

SECURE Act 2.0 picks up right where those bills left off, expanding the existing list of 10% penalty exceptions, creating new 10% penalty exceptions, and authorizing other ways for taxpayers to access retirement savings at young (pre-59 ½) ages without a penalty. Such changes include the following:

Effective immediately, Section 308 of SECURE Act 2.0 expands the Age 50 Public Safety Worker Exception (which creates an exception to the 10% early withdrawal penalty for individuals who separate from service in the year they turn 50 or older) to include private-sector firefighters. Accordingly, such taxpayers may take penalty-free distributions from defined contribution and/or defined benefit plans maintained by those employers.

Effective immediately, Section 330 of SECURE Act 2.0 expands the Age 50 Public Safety Worker Exception (to the 10% penalty) to include state and local corrections officers and other forensic security employees. Accordingly, such taxpayers may take penalty-free distributions from defined contribution and/or defined benefit plans maintained by those specific employers if they separate from service at age 50 or older.

Effective immediately, Section 329 of SECURE Act 2.0 expands the Age 50 Public Safety Worker Exception to include plan participants who separate from service before they reach age 50, but who have performed 25 or more years of service for the employer sponsoring the plan.

Notably, while one would hope that IRS regulations might provide some flexibility, a plain reading of the statute (which refers to “the” plan and not “a” plan) would seem to indicate that all 25+ years of qualifying service must be for the same employer. Thus, it would appear that an individual with 25 years of qualifying service split across 2 employers (e.g., a police officer with 15 years of service for City A, followed by 12 years of service as a police officer for State Z) would be ineligible for this treatment.

From time to time, after certain natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, wildfires, floods, tornadoes), Congress has, for a limited time, authorized affected individuals to access retirement funds without a penalty. At the time of SECURE Act 2.0’s passage, however, all such provisions had expired.

Thankfully, Section 331 of SECURE Act 2.0 eliminates the need for Congress to re-authorize such distributions for each disaster (or series of disasters) by “permanently” reinstating so-called “Qualified Disaster Recovery Distributions” retroactively to disasters occurring on or after January 26, 2021. To qualify for such distributions, an individual must have their principal place of abode within a Federally declared disaster area, and they must generally take their distribution within 180 days of the disaster.

Unfortunately, whereas disaster distributions were historically limited to a maximum of $100,000, Section 331 of SECURE 2.0 sets the maximum amount of a disaster distribution at ‘only’ $22,000. Such distributions are, however, eligible to be treated similarly to previously authorized disaster distributions in a number of ways. For instance, the income from Qualified Disaster Recovery Distributions is able to be spread evenly over the 3-year period that begins with the year of distribution (or, alternatively, to elect to include all of the income from the distribution in income in the year of distribution). In addition, all or a portion of the Qualified Disaster Recovery Distribution may be repaid within 3 years of the time the distribution is received by the taxpayer.

Section 326 of SECURE Act 2.0 creates a new 10% penalty exception for individuals who are terminally ill. For purposes of this exception, though, the definition of “terminally ill” is extremely favorable to taxpayers (to the extent such a thing can be true). More specifically, whereas for most income tax purposes, an individual is only deemed to be “terminally ill” if they have “been certified by a physician as having an illness or physical condition which can reasonably be expected to result in death in 24 months or less”, for purposes of this exception, that time frame is expanded to 84 months (7 years). Such distributions may be repaid within 3 years.

Effective for distributions made in 2024 or later, Section 314 of SECURE Act 2.0 authorizes victims of domestic abuse to withdraw up to the lesser of $10,000 (indexed for inflation) or 50% of their vested balance without incurring a 10% penalty. To qualify, the distribution must be made from a defined contribution plan (other than a defined contribution plan currently subject to the Joint and Survivor Annuity rules under IRC Section 401(a)(11) and IRC Section 417) within the 1-year period after an individual has become a victim of such abuse, and all or a portion of the distribution may be repaid within 3 years.

For purposes of this exception, the term “domestic abuse” is defined broadly to mean “physical, psychological, sexual, emotional, or economic abuse, including efforts to control, isolate, humiliate, or intimidate the victim, or to undermine the victim’s ability to reason independently, including by means of abuse of the victim’s child or another family member living in the household”. Employer plans and IRA custodians will be able to rely on an individual’s self-certification that they qualify to receive such a distribution.

Section 115 of SECURE Act 2.0 authorizes “Emergency Withdrawals” from retirement accounts, beginning in 2024. Such distributions will be exempt from the 10% penalty and may be taken by any taxpayer who experiences “unforeseeable or immediate financial needs relating to necessary personal or family emergency expenses.”

That is an extraordinarily broad definition, to the point where Congress almost seems resigned to let just about anything fly as long as it’s within reason (although distributions for an “emergency bachelorette party” probably still won’t qualify). That’s the good news. The bad news is that (perhaps owing to its near-all-encompassing definition), Congress chose to limit individuals to no more than 1 such distribution per calendar year and to cap such distributions at a maximum of $1,000.

In addition to the $1,000 annual maximum Emergency Withdrawal limit, plans will also be prohibited from allowing participants to take any subsequent Emergency Withdrawals until the earlier of the following:

Ultimately, many people may qualify to take such a distribution at some point during their lives, but the extremely limited dollar amount that is accessible via the new exception will mean that many individuals will likely still need to seek secondary exceptions to try and avoid the 10% early distribution penalty on all necessary distributions.

First effective for distributions occurring 3 years after the date of enactment (so basically 2026 and future years), Section 334 of SECURE Act 2.0 allows retirement account owners to take penalty-free “Qualified Long-Term Care Distributions” of up to the lesser of 10% of their vested balance, or $2,500 (adjusted for inflation) annually to pay for long-term care insurance.

To qualify for the exception, individuals must have either paid, or have been assessed, long-term care insurance premiums equal to or greater than their distribution in the year the distribution is made, and they must provide their plan with a “Long-Term Care Premium Statement” containing details, such as the name and Tax ID number of the insurance company, identification of the account owner as the owner of the long-term care insurance, a statement that the coverage is certified long-term care insurance, the premiums owed for the calendar year, and the name of the insured individual and their relationship to the retirement account owner.

With respect to the last item noted above – the relationship of the insured individuals to the retirement account owner – SECURE Act 2.0 permits Qualified Long-Term Care Distributions for the account owner and, provided a joint return is filed, for the retirement account owner’s spouse. The bill text also leaves the door open for the IRS to include other specified family members by Regulation, but there is no guarantee they will do so (and based on recent history, it is likely that such regulations would not be released until at least 2024).

Section 323 of SECURE Act 2.0 offers 2 items of note with respect to individuals seeking to use the existing exceptions for Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPPs), better known as 72(t) payments. First, effective immediately, it establishes a safe harbor for annuity payments to meet the 72(t) distribution requirements. Specifically, the bill states that:

…periodic payments shall not fail to be treated as substantially equal merely because they are amounts received as an annuity, and such periodic payments shall be deemed to be substantially equal if they are payable over a period described in clause (iv) and satisfy the requirements applicable to annuity payments under section 401(a)(9).

In addition, effective for 2024 and future years, the bill creates an exception to the current IRS rule that prevents individuals from making partial rollovers or transfers of accounts from which 72(t) distributions are made. Instead of the current, blanket treatment of such transfers creating a modification (and triggering retroactive 10% penalties on all pre-59 ½ distributions taken pursuant to the 72(t) plan), taxpayers will be allowed to make such transfers and rollovers provided that total distributions from the 2 accounts after the partial transfer total the amount that would have otherwise been required to have been distributed from the transferring account.

Example #5: Johnny has been taking $40,000 of 72(t) distributions from his brokerage IRA annually using the amortization method (which means his distributions are fixed for the life of the 72(t) schedule). In 2024, Johnny sees an ad for a 5-year CD at a bank paying 6% and decides that he’d like to move a portion of his current IRA to an IRA at the bank to take advantage of the 6% CD rate.

Johnny may make a partial rollover/transfer in an amount of his choosing to the bank IRA provided that, after the transfer, he continues to take a combined $40,000 out of a combination of his brokerage IRA and his bank IRA accounts.

Notably, it does not appear that distributions from the 2 accounts must be in proportion to their balances after the transfer. Rather, the text of the bill seems to indicate that as long as the total distributions from the 2 accounts (in whatever combination the account owner prefers) equal the correct 72(t) amount, no modification will have occurred.

In addition to permanently reinstating Qualified Disaster Recovery Distributions as described above, Section 331 of SECURE Act 2.0 also enables affected individuals (with their principal place of abode located within a Federally declared disaster area) to take larger loans from their qualified plans. More specifically, such participants may take loans of up to 100% of their vested balance (which are normally limited to the greater of $10,000 or 50% of the participant’s vested balance), up to a maximum of $100,000 (normally limited to $50,000). In addition, repayment dates for certain payments may be delayed for 1 year.

Beyond the significantly expanded ability to access retirement funds prior to age 59 ½ without incurring a 10% penalty (as described in detail above), to further help individuals save for unanticipated expenses at any age, effective in 2024, Section 127 of SECURE Act 2.0 creates a new type of “Emergency Savings Account”. Such accounts will not be available as standalone individual accounts, but rather, they will be linked to existing employer retirement plans with individual balances, such as 401(k) and 403(b) plan accounts.

Notably, only employees who are otherwise eligible to participate in the sponsoring employer’s retirement plan and who are not “highly-compensated” employees (i.e., they do not own more than a 5% interest in the business, they did not receive more than $135,000 in compensation in the previous year [for 2023], or they are not in the top 20% of compensation at the employer) may contribute to such accounts. Furthermore, for those employees who are eligible to participate in the new Emergency Savings Accounts, contributions must cease once the balance in the account attributable to contributions (i.e., ignoring any interest earned in the account) reaches $2,500. Employers, however, may impose lower maximum limits at their discretion.

The text of SECURE Act 2.0 offers no indication of how distributions from Emergency Savings Accounts will be allocated to the principal (contributions) and interest of such an account. Although allocating such distributions in a ratable manner is probably the most equitable policy, implementing a policy where distributions first reduce any interest (or, for that matter, principal) would be far more easily implemented and understood by plan participants. The good news, here, though, is that we shouldn’t have to wait too long to get that answer as Section 127 includes language requiring the IRS to issue regulations for Emergency Savings Accounts within 12 months!

Given that the account is intended for emergency expenses, which by their very nature are unpredictable, SECURE Act 2.0 requires that the assets in such accounts be held in a limited number of principal-protected investments, such as cash or other interest-bearing assets. In addition, plans must accept contributions in any amounts, must allow at least 1 distribution per month, and may not impose any fees for distributions on at least the first 4 distributions from such accounts each year. Furthermore, those distributions will be treated as Qualified Distributions from a designated Roth account, and thus, will be tax- and penalty-free.

Notably, most, if not all, of the above requirements could be met with a standalone type of account. So why is it that SECURE Act 2.0 requires that all such Emergency Savings Accounts be linked to an employer-sponsored retirement plan? Simply put, for contribution matching purposes, employers are required to treat contributions made to a participant’s Emergency Savings Account as though they were a salary deferral into their retirement plan. For individuals who want to prioritize building emergency savings, but who can’t afford to do so while also saving for retirement, this provision allows them to take advantage of employer matching funds in a way that would be unavailable using a standalone account like a bank account.

Absent an employee opting out, employers may also auto-enroll employees in Emergency Savings Accounts and establish a contribution percentage of up to 3% of compensation. And upon reaching the maximum contribution limit, employers may adopt default provisions that either terminate participants’ contributions or redirect them into a plan Roth account (e.g., a Roth account in a 401(k) plan). By contrast, it does not appear that such amounts can be redirected to pre-tax plan accounts by default.

Under current law, ABLE (529A) accounts may only be established for individuals who become disabled prior to turning age 26. Effective for 2026 (it’s hard to understand why they’re waiting so long to implement this change when other, dramatically more complex changes are to be implemented sooner, but what do I know?) ABLE accounts will be able to be established for individuals who become disabled prior to 46. Notably, it appears that individuals won’t have to be under 46 in 2026 to be eligible to have such an account, but rather, must only have been under 46 at the time they became disabled. This is significant because many disabilities – and in particular, many mental health conditions that can cause a person to become disabled – develop after age 25, which means that individuals who suffered from such conditions were locked out of saving to an ABLE account under previous law.

Example #6: 15 years ago, while trying to chase a dormouse, Barbara tripped and fell. Her resulting injuries left her disabled and unable to work. At the time, Barbara was 38 years old. Thus, to date, Barbara has been ineligible to be the beneficiary of an ABLE Account.

In 2026, Barbara will turn 57. However, despite being well over age 45 at the time, Barbara will be eligible to be named the beneficiary of an ABLE account because she was younger than 46 at the time she became disabled.

Section 309 of SECURE Act 2.0 provides significant income tax relief for certain disabled first responders. Qualifying First Responders are law enforcement officers, firefighters, paramedics, and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) who receive service-connected disability and retirement pensions.

Currently, disabled first responders who receive a disability pension or annuity related to their service are generally able to exclude those amounts from income. However, once they reach their regular retirement age, their disability pension becomes a retirement pension (similar to the way that disability benefits received from Social Security automatically convert to retirement benefits at Full Retirement Age) and is no longer excludable from income. Thus, at the proverbial flip of a switch, such disabled first responders effectively trade a tax-free income stream for a regular taxable pension.

SECURE Act 2.0 seeks to address this disparity by introducing an “excludable amount” that effectively allows such individuals to carry on the tax-favored disability payment throughout their lifetime. Specifically, the excludable amount is defined as the income received in the year before retirement age (those who only received payments for part of the year will annualize the amount). Thus, in simple terms, whatever the nominal amount a qualifying first responder received as tax-free payments prior to their retirement age, they will be able to continue receiving as tax-free payments after their retirement age.

Notably, while this provision is not effective until 2027, it does not appear that there is any requirement that payments need to begin after that time to qualify. Thus, many former first responders who are currently receiving taxable retirement benefits, but who previously received tax-free disability payments in connection with their service, will see a significant increase in net-after-tax income beginning in 2027.

Example #7: Lowell is a 68-year-old former paramedic who became disabled during the course of duty nearly 20 years ago. For many years, until he reached his retirement age under his pension plan, he received $60,000 of annual disability payments from the plan that he was able to exclude from income. Later, when he reached his retirement age, those disability payments ceased and ‘regular’, fully taxable retirement benefits began to be paid.

Now, as a result of changes made by SECURE Act 2.0, beginning in 2027, Lowell will, once again, be able to exclude $60,000 of payments from his annual gross income.

In perhaps an unanticipated outcome, from the language of Section 331 of SECURE Act 2.0, it seems that if an individual continues to work as a first responder beyond their plan’s retirement age and then becomes disabled, they would not be eligible for the same exclusion treatment. Perhaps Congress will address this potential inequity in the future.

Taxpayers have long been able to create and fund certain SEP IRA accounts after the end of the year (up until the individual tax filing deadline, plus extensions) for the previous year. For instance, a SEP IRA first created in June 2022 could have received contributions for 2021 (even though no plan actually existed at that time). The original SECURE Act expanded that retroactive treatment to other employer-only funded plans, such as Profit-Sharing Plans and Pension Plans.

Effective for plan years beginning after the date of enactment (effectively, for plans that are established in 2023 or later), Section 317 of SECURE 2.0 now takes that ability one step further by allowing sole proprietors, as well as those businesses treated as such under Federal law for income-tax purposes (e.g., Single Member LLCs), to establish and fund solo-401(k) plans with deferrals for a previous tax year, up to the due date of the individual’s tax return (although notably without extensions).

Accordingly, while historically there hasn’t been any urgency to establish solo-401(k) plans early in the year, such consideration should now be given to the extent an individual is a sole proprietor, and retroactive deferrals for the prior year would be advisable.

If it isn’t already abundantly clear, the rules for retirement accounts are incredibly complicated. To that end, it should come as no surprise that when it comes to such accounts, mistakes are pretty common. Thankfully, for many retirement account owners, SECURE Act 2.0 includes a host of changes designed to limit the impact of various retirement account mistakes.

Effective for 2023 and future years, Section 302 of SECURE Act 2.0 reduces the 50% penalty for an RMD shortfall to 25%. If, however, the shortfall is rectified within the “Correction Window,” then the penalty is further reduced to only 10%.

Per SECURE Act 2.0, the “Correction Window” is defined as beginning on the date that tax penalty is imposed (so, generally January 1 st of the year following the year of the missed RMD), and ends upon the earliest of the following dates:

Although these changes do not preclude a taxpayer from seeking to have the penalty abated altogether, for smaller missed distributions the timely fixed missed RMD penalty dropping to just 10% may give some individuals an incentive simply to pay the penalty and move on.

Section 313 of SECURE Act 2.0 resolves an issue that has haunted some individuals since a 2011 Tax Court decision. In Paschall v Commissioner (137 T.C. 8, 2011), the Court ruled that for purposes of assessing IRA penalties, the statute of limitations on such penalties does not begin until Form 5329 – the form on which such penalties are reported – is filed. The problem, though, is that if you don’t realize a mistake has been made, you have no reason to file Form 5329, and thus such mistakes generally have an indefinite statute of limitations.

In an effort to simplify matters and to provide some finality to taxpayers who have made certain mistakes with their retirement accounts, effective immediately, the statute of limitations 'clock' for an RMD shortfall (technically referred to as a tax on “excess accumulations”), as well as for most excess contributions, will begin ticking with the filing of Form 1040 for the year in question (rather than Form 5329). Furthermore, to the extent that an individual is not required to file Form 1040, the statute of limitations 'clock' for such penalties will begin ticking upon the tax filing deadline.

Section 313 of SECURE Act 2.0 further specifies that for purposes of assessing the penalty for an RMD shortfall, the statute of limitations is 3 years. By contrast, the statute of limitations for assessing the penalty for excess contributions is 6 years (unless the excess contribution is in relation to the acquisition of property for less than its fair market value, in which case the statute of limitations will remain indefinite unless Form 5329 has been filed).

Section 305 of SECURE Act 2.0 could have sneakily important long-term ramifications for many IRA owners. To date, the Employer Plans Compliance Resolutions System (EPCRS) has primarily been used to address… well… issues with employer plans!

Going forward, however, SECURE Act 2.0 instructs the IRS to, within 2 years of enactment, issue new guidelines to expand the use of EPCRS to IRA mistakes as well. While the ultimate list of IRA mistakes that are eligible to be fixed in this manner is likely to be far broader, Section 305 specifically requires the IRS to consider how EPCRS could be used to provide waivers of the penalty for an RMD shortfall (where appropriate), as well as how distributions from an inherited IRA to non-spouse beneficiaries attributable to an inadvertent error by a service provider can be replaced into the IRA.

The bill will also expand the use of EPCRS for more employer plan issues as well. To that end, Section 305 instructs the IRS to consider how the program can be used to rectify inadvertent plan loan errors.

Interestingly, Section 322 of SECURE Act 2.0 provides confirmation and/or clarification that, beginning in 2023, when a Prohibited Transaction occurs within an IRA account (which generally results in being deemed a full distribution from the IRA and a loss of its tax-favored status), only that account is deemed distributed. Admittedly, this provision is a bit of a head-scratcher, since that has always been the way it’s been enforced.

Perhaps someone at the IRS felt that interpretation was incorrect, and the Service was considering a reinterpretation. Or perhaps it’s quietly been a known issue that folks at the IRS were just waiting for Congress to formally correct. It’s hard to say, but regardless of the reason for its inclusion in SECURE Act 2.0, it’s good to have the ultimate impact for IRAs spelled out in black and white language (although of course, avoiding a prohibited transaction in the first place is always a much better approach!).

SECURE Act 2.0 has been heavily championed by the insurance industry for a variety of reasons, but mostly due to its various changes and clarifications of rules related to annuities and, in particular, those annuities held within qualified accounts. To that end, annuity-related changes made by SECURE Act 2.0 include the following:

Effective immediately, Section 202 repeals the 25%-of-account-balance limitation for such contracts, and increases the maximum amount that can be used to purchase such products to $200,000 (up from $145,000 in 2022 and what would have been $155,000 for 2023). In addition, retroactive to the establishment of QLACs in 2014, such contracts are allowed to offer up to a 90-day free-look period and may continue to make joint lifetime payments to divorced couples who elected such payout options previously, while they were married.

Effective immediately, income annuities held within qualified plans and IRAs are able to offer additional benefits without violating some very arcane actuarial rules in IRS Regulations related to RMDs. More specifically, Section 201 of SECURE Act 2.0 provides that the following benefits/contract options will not cause an annuity to be in violation of the RMD rules:

Section 203 of SECURE Act 2.0 instructs the IRS to amend its Regulations such that, effective 7 years after enactment, variable annuities and Variable Universal Life (VUL) policies are eligible to include “Insurance Dedicated ETFs” in their investment lineup. In effect, such investments will be to ETFs what existing subaccounts today are to mutual funds.

SECURE Act 2.0 is absolutely packed with additional plan-related changes. Some changes will primarily impact only plan administrators. Others are changes that could have relevance for small business owners seeking to establish, update, or change an existing plan. While still others will be relevant to the end clients who participate in such plans. Key plan-related changes include (but are not limited to) the following:

Incredibly, even after all of the provisions covered above, there are still a substantial number of provisions contained in SECURE Act 2.0 that have yet to be covered in this article. While not completely exhaustive, the list of provisions in the bill of which advisors should be aware includes the following:

Whenever there is a significant piece of new legislation, one of the most common questions financial professionals receive from those they closely advise is, “Is there anything in the bill on [fill in the blank]?” It’s hard enough to rifle through hundreds (or thousands) of pages of legislative text to find a provision that one is certain is actually in the bill. Sifting through a bill that size to determine what isn’t there is exponentially more challenging (as proving a negative usually is). To that end, advisors, tax preparers, and other financial professionals should be aware that SECURE Act 2.0 contains no provisions that:

Finally, perhaps most noteworthy of all, there is absolutely nothing in SECURE Act 2.0 that provides any sort of simplification of the rules surrounding retirement accounts. Taxpayers are all but guaranteed to continue to have a nearly endless stream of questions with respect to this complicated area. Accordingly, advisors who exhibit a strong command over such rules, including the many changes made by SECURE Act 2.0, will be best positioned to guide individuals in the years to come and to win the lion’s share of new retirement-related business.

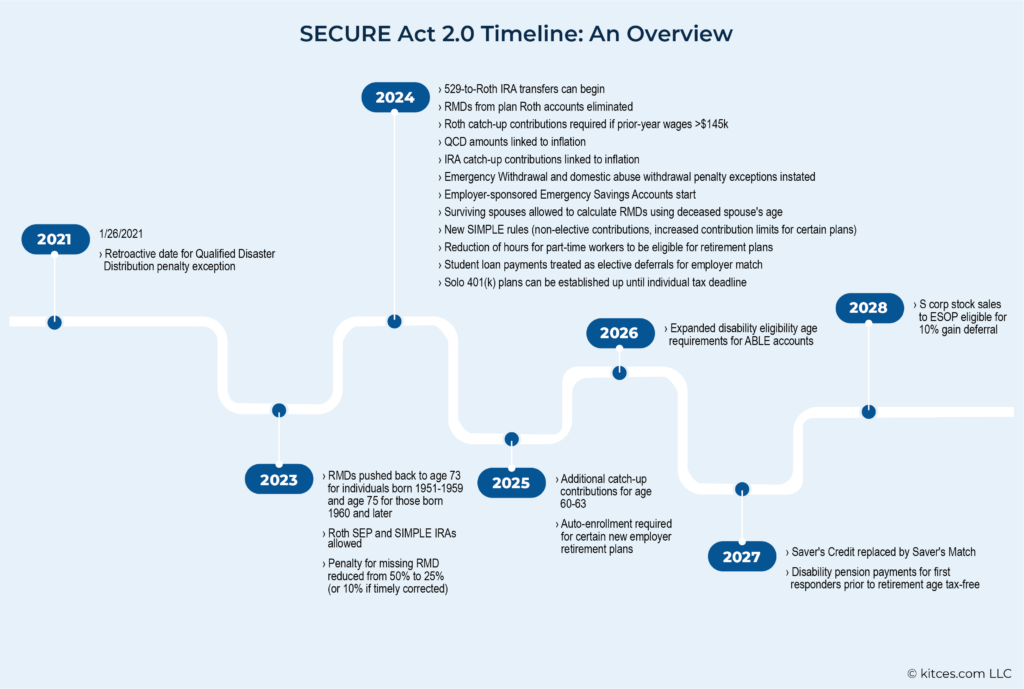

Ultimately, as much additional complexity as SECURE Act 2.0 adds to the retirement planning landscape, one of the trickiest things about the new legislation might be simply keeping track of the dates that all of its many provisions take effect. Because while the bulk of the provisions will be effective in 2023 or 2024, some also take effect immediately upon enactment (which would make them effective on December 23, 2022), others are pushed back farther to 2026, 2027, or 2028, while one (the reinstatement of Qualified Disaster Distributions) takes effect retroactively to disasters occurring on or after January 26, 2021. As shown below, there is a long and winding road until all of SECURE Act 2.0's provisions come into effect.

Meanwhile, advisors can focus on understanding which components of SECURE Act 2.0 will impact their clients the most (which might include the delayed RMD dates, the Rothification of catch-up contributions for high-wage earners, and/or the elimination of RMDs from plan Roth accounts). Additionally, advisors can also identify opportunities for planning strategies that could prove valuable for their clients in the future (such as making 529-to-Roth IRA transfers, having surviving spouses elect to be treated the same as their deceased spouse for RMD purposes, or electing Roth employer contributions in a self-employed client's SEP IRA). Ultimately, the silver lining of SECURE Act 2.0's complexity is that it provides advisors with even more ways to add value for their clients!

Quality? Nerdy? Relevant?

We really do use your feedback to shape our future content!